Recent progress on alloy-based anode materials for potassium-ion batteries

Abstract

Potassium-ion batteries (PIBs) are considered as promising alternatives to lithium-ion batteries due to the abundant potassium resources in the Earth’s crust. Establishing high-performance anode materials for PIBs is essential to the development of PIBs. Recently, significant research effort has been devoted to developing novel anode materials for PIBs. Alloy-based anode materials that undergo alloying reactions and feature combined conversion and alloying reactions are attractive candidates due to their high theoretical capacities. In this review, the current understanding of the mechanisms of alloy-based anode materials for PIBs is presented. The modification strategies and recent research progress of alloy-based anodes and their composites for potassium storage are summarized and discussed. The corresponding challenges and future perspectives of these materials are also proposed.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

With the rapidly growing demand for energy globally, unrenewable traditional fossil fuels, such as coal, oil and gas, are facing depletion[1-9]. Clean and renewable energy resources, such as solar, wind and tidal energy, are among the most abundant and promising available resources to take the place of fossil fuels in the future. It is necessary to combine electrical energy storage devices with these renewable energies. Rechargeable lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are high-energy electrical energy storage devices that have been commercialized for around three decades. LIBs cannot only be used with natural clean renewable energies but are also ubiquitous in our daily lives for powering electronics, including cell phones, electric cars and laptops. However, their high-cost resources and the uneven distribution of lithium in the Earth’s crust make it imperative to develop alternatives to LIBs with comparable performance[10-12].

Potassium-ion batteries (PIBs) are possible alternatives to LIBs. Compared to lithium resources in the Earth’s crust, potassium resources are significantly more abundant in the Earth’s crust at ~1.5 wt.%. The price of potassium salts, such as K2CO3, is far less compared to Li2CO3. In addition to the lower cost of potassium resources, inexpensive aluminum current collectors can be used together with PIBs to offer a low-cost method based on economical salts[13-15]. In addition, potassium ions exhibit much weaker Lewis acidity, which results in smaller solvated ions compared to lithium and sodium ions. Therefore, the ionic conductivity of solvated K+ is higher than that of lithium and sodium ions[16,17]. In addition, the lower energy required to dissolve potassium ions also results in their fast diffusion kinetics.

Similar to LIBs and sodium-ion batteries (SIBs), the study of cathode materials for PIBs mainly includes layered transition metal oxides, Prussian blue analogs (PBAs) and polyanionic compounds. Layered transition metal oxides based on KxMO2 (x ≤ 1, M = Co, Cr, Mn, Fe or Ni) deliver high capacity but face the critical problems of multiple plateaus and large structural changes during potassium-ion intercalation/deintercalation[18,19]. The chemical formula of PBAs is represented as

The search for anode materials is also an important part of PIB research and development. Commercialized graphite has been widely applied in LIBs; however, it is not an ideal anode candidate. Even though graphite has a theoretical capacity of ~280 mAh g-1 from the formation of KC8[28,29], the large radius of the potassium ions results in sluggish diffusion kinetics and the formation of an unstable SEI. Therefore, graphite anodes deliver limited experimental capacity and cycling life in PIBs. As a result, it is crucial to develop high-performance anode materials with high specific capacity and long cycling life for practical application. In the past five years, there has been a large volume of research regarding electrode materials for PIBs, including metal-organic structure design[30,31] for electrodes and the modification of electrode surfaces[32,33]. However, there have been few review papers that focus on anode materials for PIBs, especially on high-performance alloy-based anode materials, including their modification and mechanisms in PIBs[34]. In this review, we comprehensively summarize the current understanding of alloy-based anode materials and their composites for PIBs, as shown in Figure 1, including their mechanisms, modification strategies and recent research progress for potassium storage. The challenges and future perspectives corresponding to these materials are also presented.

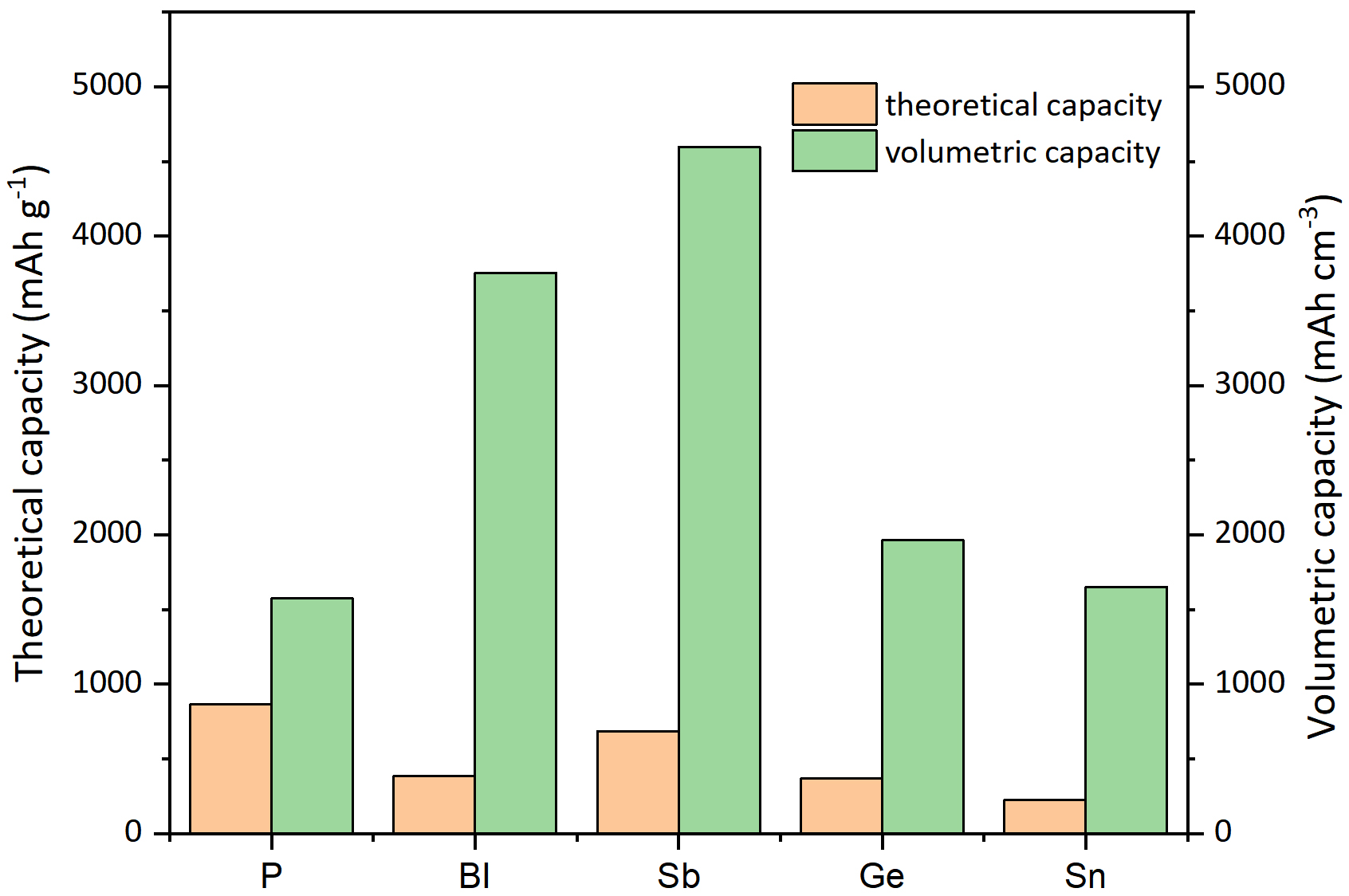

Alloy-based elements can deliver high-capacity anode materials via the formation of potassium-rich materials. For example, Bi has a high theoretical capacity of 385 mAh g-1 PIBs. Sb has a high theoretical capacity of 687 mAh g-1. P has the highest theoretical capacity among alloy-based anodes in PIBs of

Potassium storage mechanism of alloy-based anode materials for PIBs

Potassium storage in anode materials for PIBs can be classified into three categories: intercalation, alloying and conversion. The intercalation reaction results in a smaller volume change and higher reversible capacity than the other potassium storage mechanisms. During the interaction reaction, potassium ions are inserted into the anode material and form a new phase. This reaction usually takes place in materials with a layered structure, such as graphite[35,36] and K2Ti4O9. The alloy-based anode material SnS2 undergoes an intercalation reaction in the first step and conversion and alloying reactions in the following steps. The intercalation reaction can be expressed as MxNy + aK+ + ae- ↔ KaMxNy. Typical intercalation reactions deliver high reversible capacity because of the low volume change of the crystal during the electrochemical reaction. Due to the large radius of the potassium ion, however, anode materials with an intercalation-type potassiation process experience a larger volume change and have less reversible capacity in their performance in LIBs and SIBs.

Compared to the intercalation reaction, alloying-reaction materials undergo a larger volume change and have higher theoretical capacities. Alloying-type materials react with K to form the binary compound KxM. The reaction process can be expressed as aM + bK+ + be- ↔ KbMa. In this reaction, M represents Sn, Bi, Sb, P or Ge. These alloying-type materials can form binary metallic materials that undergo conversion-alloying reactions, in which the compound decomposes and further alloys with potassium. For example, Sn4P3 undergoes the following reaction: Sn4P3 + 11K ↔ 4KSn + 3K3P[26]. Similarly, Sb2Se3 goes through the following conversion-alloying reaction: Sb2Se3 + 12K++ 12e- ↔ 3K3Sb + 2K2Se3[27].

These conversion-alloying type reactions can be expressed as MxNy + (xn + ym)K+ + (xn + ym)e- ↔ xKnM + yKmN. Similarly, the metallic compounds that go through conversion-alloying type reactions also deliver high theoretical capacities. For example, Sn4P3 delivers a high capacity of 585 mAh g-1 while the experimental capacity is ~384 mAh g-1.

Challenges

Although alloying-type anode materials deliver high theoretical capacities, their practical reversible capacities are far below their theoretical capacities. The severe volume change causes capacity decay, poor cycle life, inferior rate performance, sluggish kinetics and limited cycling lifespans.

The initial capacity is a key factor, especially for the anode material, which contributes to the energy density of the full cell. The significant volume changes during the discharge-charge processes cause pulverization of the active materials, which results in discontinuous particles. Due to the large resistance within the particles, the potassium ions cannot be fully extracted, which results in irreversible capacity and low Coulombic efficiency. In addition, the stress generated in the electrode during the discharge process damages the SEI, resulting in its breakdown and the reformation of a new SEI film. In addition, the pulverized particles inevitably go through crystallization and aggregation, which increase the diffusion length of the potassium ions and also lead to irreversible capacity loss. The decreasing reversible capacity results in a rapid capacity drop and short cycling life.

ALLOY-BASED ANODES FOR PIBS

Phosphorus-based anode materials

Among alloying-typed anode materials, phosphorus is very attractive because it has a high theoretical capacity of 2596 mAh g-1 in LIBs and SIBs and a low work potential (~0.3 V vs Na/Na+). In PIBs, it has a high theoretical capacity of 2590 mAh g-1 based on the three-electron alloying mechanism.

Mechanism of phosphorus and metal phosphides in PIBs

There are three main types of phosphorus in nature, namely, white phosphorus (WP), red phosphorus (RP) and black phosphorus (BP). WP is toxic and has a low ignition point, so it is unsuitable as an electrode. RP exists in a non-crystalline form and has a low conductivity of 10-12 S m-1. BP is a layered structure semiconductor material, which has a wide interlayer spacing of 5.2 Å and a higher conductivity at 300 S m-1. BP has a high theoretical capacity of 2600 mAh g-1 for LIBs and NIBs and also has a low diffusion barrier of 0.035 eV for Li+ and 0.064 eV for Na+, which makes it a promising anode material to explore for PIBs. There are two interlayer migration paths: zigzag- and armchair-type migration paths. The zigzag path has a much lower energy barrier. Based on calculations, K has the lowest energy barriers for both paths compared to Li and Na, which endow PIBs with fast discharging and charging. The corresponding voltage can be calculated based on the following equation:

where V, μ, q, G, e and N are the voltage, chemical potential, charge, absolute electron charge, Gibbs free energy and the number of K ions, respectively.

Thus, the calculated potassium-ion insertion process is BP → K2P3 → KP. A previous study of the potassiation mechanism indicated that the final product was KP[36-39], which was first revealed by the group of Glushenkov. Compared to this result, a further study by Jin et al. used X-ray absorption near-edge structure and ex-situ X-ray diffraction (XRD) methods to analyze the mechanism[38]. The results demonstrated that the potassiation process of BP was K+ + P + e- → KP. An RP-based nanocomposite was studied by the group of Xu[39]. The composite was synthesized by anchoring RP nanoparticles on a 3D nanosheet framework. The reaction mechanism of the composite was explored by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED). Based on the first cycle reaction results, KP was proposed to be the final product, corresponding to a capacity of 865 mAh g-1, which is lower than the theoretical capacity. Yu et al. synthesized an RP/carbon nanocomposite by embedding RP into free-standing nitrogen-doped porous hollow carbon[40]. Using in-situ Raman spectroscopy and ex-situ XRD, the final product in the discharge process was directly proved to be K4P3.

One challenge for BP and RP in the potassiation process compared to lithiation is the lower capacity. A BP-graphite composite had only 42% of the capacity for lithiation. The other issue is their large volume expansion. BP-graphite showed a 200% volume expansion when discharged to 0.01 V[41].

The large volume expansion during the potassiation process and low conductivity of RP severely limit the application of phosphorus-based anode materials in PIBs. To overcome this, active (Sn, Ge and Se) and inactive metals (Co, Fe and Cu) have been hybridized with P to form phosphides. During the discharge process, the decomposed nanocrystals form a conductive and elastic matrix to enable faster charge transfer and hinder volume expansion. In addition, the active metals become alloyed with potassium ions and also make contributions to the capacity. Metal phosphides can be classified into two categories based on active and inactive metals. For the inactive metals, the storage mechanism reaction can be summarized as follows:

For the active metal phosphides, the reaction can be summarized as follows:

The original phosphide MxPy decomposes and the phosphorus is converted into K3-xP, while inactive metal M is dispersed as a matrix and active metal M is also alloyed with K to produce KnM.

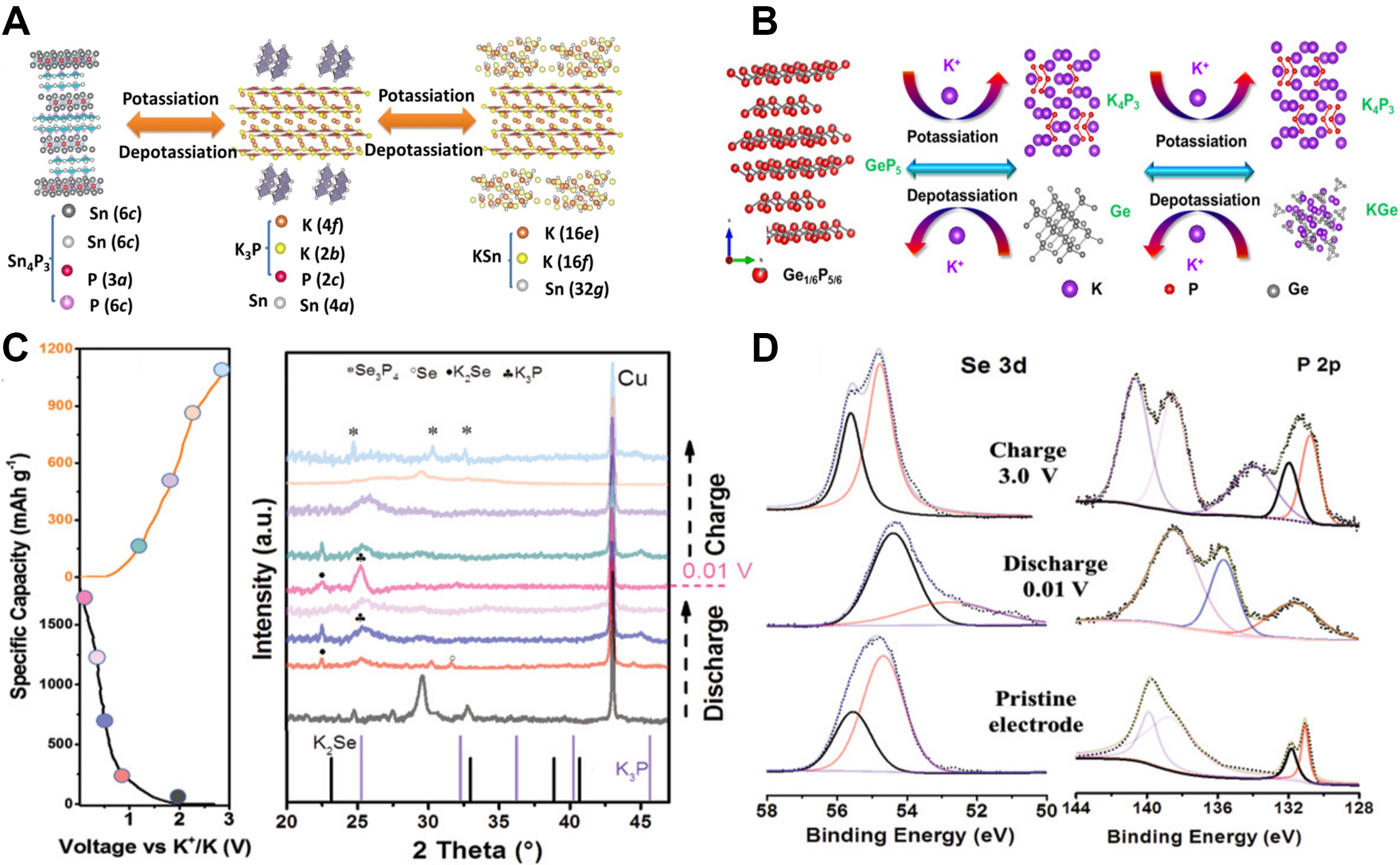

Unlike phosphides in LIBs and SIBs, to date, the reported phosphide potassiation mechanisms are conversion-type mechanisms. For example, the electrochemical reaction of Sn4P3 in PIBs is a typical conversion reaction, as first studied by the group of Guo based on an in-operando synchrotron XRD investigation. In the initial discharge stage, Sn4P3 breaks into Sn particles and the P component precipitates in an amorphous form to react with potassium. Sn is alloyed with K and the KSn phase is formed. K3P11 further reacts with K, starting from ~0.17 V. The reaction process could be divided into three steps, namely, Sn4P3 + (9-3x)K ↔ 4Sn + 3K3-xP, 23Sn + 4K ↔ K4Sn23 and K4Sn23 + 19K ↔ 23KSn, as shown in Figure 3A[42]. The Sn4P3@carbon fiber electrode delivered cycling stability and a high-rate capability of 160.7 mAh g-1 after 1000 cycles at a current density of 500 mA g-1. Like Sn4P3, GeP5 also has a similar conversion reaction. Based on in-operando synchrotron XRD measurements, a two-step reaction was observed as follows: GeP5 + 20/3K ↔ 5/3K4P3 + Ge, Ge + K ↔ KGe. These two steps can be summarized into one equation as follows: 3GeP5 + 23K ↔ 5K4P3 + 3KGe[43]. This potassiation process is shown in Figure 3B. Similarly, in the first stage of the reaction, GeP5 decomposes into Ge and P particles and the P component reacts with K to form K4P3. In the following stage of the reaction, Ge alloys with K to form KGe. Se is also an active element that can form

Figure 3. (A) Potassiation/depotassiation process in Sn4P3/C[42]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (B) Potassiation/depotassiation process in GeP5 electrodes[43]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. (C) Discharge/charge curves of Se3P4@C and XRD patterns of Se3P4@C anode in the first cycle at different cut-off voltages. (D) XPS spectra of Se3P4@C electrode at different cut-off voltage states[44]. Copyright 2020, Wiley VCH.

In summary, until now, the reported phosphide potassiation mechanisms have been conversion-type mechanisms, which are different from phosphides in SIBs and LIBs. In the first discharge step, the phosphide decomposes into metal and phosphorus. After the anode has been fully discharged, the active metal reacts with K and forms KnM compounds, with the phosphorus alloyed with K to form KmP.

Modification strategies for P and phosphides

Carbon materials, including nanosheets[39], nanofibers[40] and graphite[45], have been applied in phosphorus and phosphides. The hybridization of phosphorus and phosphides with carbon materials has been proven to be an efficient method to improve the electrochemical performance. The introduction of carbon can enhance the electron conductivity, accommodate the volume change and also shorten the potassium-ion diffusion length. Furthermore, the induced carbon can form covalent P-C interfaces to prevent edge reconstruction and ensure ion insertion and diffusion[35]. In addition, the formation of P-C bonds[46-49] by hybridizing BP with carbon materials can afford high capacity and cycling stability in PIBs by connecting particles. This can also be seen from the work of Verma et al., where the electrochemical performance of SnP3 was efficiently improved by hybridizing with carbon[50]. The electrode maintained a reversible capacity of 225 mAh g-1 after 80 cycles, which was an improvement compared to the previous rapid capacity drop of the SnP3 electrode in cycling performance. Similarly, the group of Zhu[51] designed a flexible and hierarchically porous 3D graphene/FeP composite via a one-step thermal transformation strategy. The interconnected porous conducting network sufficiently buffered stress due to the nano-hollow spaces and greatly promoted the charge transfer. Thus, the composite delivered a high-capacity retention of 97.2% over 2000 cycles at a high rate of 2 A g-1 in PIBs.

Synthesizing nanostructured phosphorus and phosphide materials, such as yolk-shell structures[52], hollow structures and nanowires, is another efficient method to improve the electrochemical performance of phosphide and phosphorus anodes. For example, Yu et al. designed a one-dimensional electrode by embedding RP into free-standing nitrogen-doped porous carbon nanofibers[40]. This design was favorable for reducing the absolute strain and preventing pulverization and agglomeration. As can be seen from their images, during potassiation, the thickness changed from 74 to 93 nm with a volume expansion of only 26%. Because of its nanowire structure, the composite exhibited a high reversible capacity of 465 mAh g-1 after 800 cycles at a high current density of 2 A g-1. The yolk-shell and hollow structures have void space that can accommodate the significant volume change, so that particles can expand without deforming the carbon shell during potassiation[52]. The potassium-ion transport in BP is mostly in the armchair direction, as shown in Figure 4A and B. The potassiation process includes several steps with the formation of binary phosphide, as displayed in Figure 4C. Figure 4D shows that the composite delivered stable cycling performance with a reversible capacity of 205 mAh g-1 after 300 cycles. A comparison of the electrochemical performance of phosphides and their composites is shown in Table 1.

Figure 4. (A) Time-lapse TEM images for single RP@N-PHCNFs, where PHCNFs are porous hollow nanofibers, during potassiation process. (B) Charge/discharge profiles of RP@N-PHCNF electrode at various current densities and cycling performance of

Summary of electrochemical performance of P-based anodes for PIBs

| Anode materials | Synthesis method | Modification methods | Redox potential (vs. K/K+) | Current density (mA g-1) | Initial capacity (potassiation) (mAh g-1) | Initial depotassiation | 1st CE | Reversible capacity | Best rate capability | Electrolyte | Ref. | |

| BP | BP/graphite | Vaporization-condensation | Hybridized with graphite | ~0.5 V | 250 | 1430 | 600 | 42% | 340 mAh g-1 after 100 cycles at current density of 0.75 A g-1 | 340 mAh g-1 at 750 mA g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in EC:DEC | [38] |

| RP | RP/carbon nanosheet | Heat treatment | Hybridized with carbon nanosheets/design of 2D nanostructure | 0.16-1.0 V | 100 | 1212 | 715 | 59% | 427.4 mAh g-1 after 40 cycles at current density of 100 mA g-1 | 323.7 mAh g-1 at 2000 mA g-1 | 0.8 M KPF6 in EC:DEC | [39] |

| Yolk-shell FeP/C | Hybridized with carbon/design of 3D nanostructure | 0.05-1.2 V | 100 | 561 | 264 | 47% | 205 mAh g-1 after 300 cycles | 37 mAh g-1 at 2000 mA g-1 | 0.8 M KPF6 in EC:DEC | [52] | ||

| Phosphide (inactive metal) | CuP2/Carbon nanosphere | Wet chemical and heat treatment | Hybridized with carbon/design of 2D nanostructure | 100 | ~700 | ~490 | ~70% | 400 mAh g-1 over 300 cycles | 170 mAh g-1 at 2 A g-1 | 4 M KFSI in DME | [53] | |

| CoP/C | Heat treatment | Hybridized with carbon | 50 | 706 | 301 | 42.7% | 40 mAh g-1 at 1000 mA g-1 after 400 cycles | 106 mAh g-1 at 1000 mA g-1 | 1 M KPF6 EC:PC | [54] | ||

| Phosphide (active metal) | SnP3/C | Mechanical milling | Hybridized with carbon | 0.01-0.8 V | 50 | 697 | 410 | 58.8% | 408 mAh g-1 after 50 cycles | 225 mAh g-1 at 500 mA g-1 | 0.75 M KPF6 EC:DEC | [50] |

| Se3P4/C | Mechanical milling and heat treatment | Hybridized with carbon | 1.3-1.9 V 0.37 V | 50 | 1505 | 1036 | 68.9% | 783.4 mAh g-1 after 100 cycles at 100 mA g-1 | 388 mAh g-1 at 1000 mA g-1 | 0.8 M KPF6 EC:DEC:FEC | [44] | |

| Sn4P3/C | Mechanical milling | Hybridized with carbon | 0.01-1.15 V | 50 | 588.7 | 384.8 | 65% | 307.2 mAh g-1 at 50 mA g-1 after 50 cycles | 221.9 mAh g-1 at 1000 mA g-1 | 1 M KPF6 EC:DEC | [51] | |

| Sn4P3/carbon fiber | Mechanical milling and electrospinning | Hybridized with carbon/design of nanostructure | 0.01-0.5 V | 50 | 803 | 514 | 64% | 403 mA g-1 at 50 mA g-1 after 200 cycles | 160.7 mA g-1 after 1000 cycles at 500 mA g-1 | 1 M KFSI EC:DEC | [55] | |

| Sn4P3/C | Wet chemical and heat treatment | Hybridized with porous carbon/design of nanostructure | 0.01-0.4 V 1.1-1.6 V | 100 | 845 | 431 | 51% | 315 mA g-1 at 1000 mA g-1 after 100 cycles | 186 mAh g-1 at 2000 mA g-1 | 0.8 M KPF6 EC:DEC | [56] | |

| GeP5 | Mechanical milling | Nanostructural design | 50 | 2038 | 934 | 45.81% | 495.1 mA g-1 at 50 mA g-1 after 50 cycles | 213 mA g-1 at 500 mA g-1 after 2000 cycles | 1 M KFSI EC:DEC | [43] |

The theoretical capacity of phosphorus in PIBs is 2596 mAh g-1 based on the three-electron alloying mechanism; however, the experimental capacity varies with different final products. There are currently three known types of final potassiation products of phosphides, namely, KP, K4P3 and K3P. In addition, the final and intermediate products of phosphides in PIBs are different even though the reactions are typically conversion-alloying mechanisms. Due to the significant volume change during the potassiation processes of phosphorus and phosphides and the low conductivity of phosphorus, various modification methods have been applied. Synthesizing nanostructures, such as yolk-shell, nanowire and hollow structures, and hybridization with graphite, graphene, nanotubes and porous carbon have significantly improved the electrochemical performance.

Bi-based electrodes for PIBs

Bi is an attractive low-cost and non-toxic anode material. Due to its large interlayer spacing (d) along the

K-ion storage mechanism of Bi-based anodes

Based on the K-Bi equilibrium diagram with the KBi2, K3Bi2, K3Bi(α), K3Bi(β) and K5Bi4 phases, Huang et al. first studied the potassium-ion storage mechanism in Bi microparticles[57]. They revealed stepwise Bi → KBi2 → K3Bi2 → K3Bi dealloying-alloying electrochemical processes after the initial surface potassiation. Similarly, a bulk Bi anode delivered a reversible three-step reaction during cycling, with K3Bi as the fully discharged product[58]. Bi microparticles have the same mechanism as shown in Figure 5A and B, with K3Bi as the final discharged product. As shown in Figure 5C, the observation of K5Bi4 during the potassiation process was first reported by the group of Guo[59]. They found a different transition process, in which the potassiation of Bi nanoparticles proceeds through a solid-solution reaction, followed by a two-step reaction, corresponding to Bi → Bi(K) and Bi(K) → K5Bi4 → K3Bi. Xie et al. constructed dual-shell-structured Bi box particles and microsized Bi, which had different appearances during the transformation from K3Bi2 to K3Bi under a low current density[60]. In the case of nanostructured Bi, the K3Bi2 phase went through a transformation to K3Bi, as shown in Figure 5D. In comparison, the microstructure of Bi retained the K3Bi2 phase and no significant K3Bi phase was formed. Interestingly, when the current was increased, no significant K3Bi2 or K3Bi phase was observed, indicating that the main mechanism was a surface-driven adsorption reaction under a high current.

Figure 5. Different potassiation and depotassiation mechanisms of Bi. (A) Alloying and dealloying processes in microparticle Bi electrode[57]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (B) Discharge/charge curves for XRD patterns and XRD patterns with Rietveld refinement of intermediates of porous Bi electrode[58]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (C) Ex-situ XRD patterns collected at different charge/discharge states with refined lattice parameters and proposed potassiation/depotassiation mechanism of Bi@reduced graphene oxide (rGO) electrode[59]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (D) Operando XRD pattern with superimposed voltage profiles of C@DSBC and microsized Bi[60]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier.

The study of the potassiation mechanism in Bi-based alloys has also attracted significant attention. The reaction process includes two stages. The first step was an intercalation reaction: Bi2S3 + xK+ + xe- → KxBi2S3. The second step was a conversing-alloying reaction: KxBi2S3 + (6-x)K+ + (6-x)xe- → 3K2S + 2Bi and Bi +3K++ 3e- →K3Bi[61]. Chen et al. also studied the reaction mechanism of Bi2Se3 using in-situ operando XRD[62]. The results indicated that the potassiation process also undergoes an intercalation reaction in the first steps, with a conversion-alloying reaction in the following step. The electrochemical process was summarized as follows: 2Bi2Se3 + 4xK+ + 4xe- → 4KxBiSe3, KxBiSe3 + (6-x)K+ + (6-x)e- → 3K2Se + Bi and i + 3K++ 3e- → K3Bi[62].

The above results illustrate the diverse potassiation mechanisms. The differences in the potassiation and depotassiation processes were mainly because of the following reasons: (1) the mechanisms are strongly dependent on the sizes of the materials; (2) the unique structure of the Bi-based anodes; and (3) the current density of the electrochemical reaction. The small particle sizes, well-constructed nanostructure and low current density resulted in full potassiation and transformation that involved several transition phases.

Modification strategies for Bi-based anodes

The main challenge for Bi-based anode materials is the pulverization and fracturing of the electrode during the cycling process that are driven by the significant volume changes, resulting in capacity fading.

To improve the electrochemical performance of Bi, various methods have been applied. One method is to combine Bi with carbon materials. Various porous carbon materials have been applied, such as porous graphene[63] and carbon nanosheets[64]. Both of these porous carbons were synthesized using freeze drying assisted by a pyrolysis method. The Bi/macroporous graphene composite delivered an excellent rate performance of 185 mAh g-1 at a high current density of 10 A g-1. This was because the 3D interconnected macroporous graphene framework could provide robustness to maintain the structural stability.

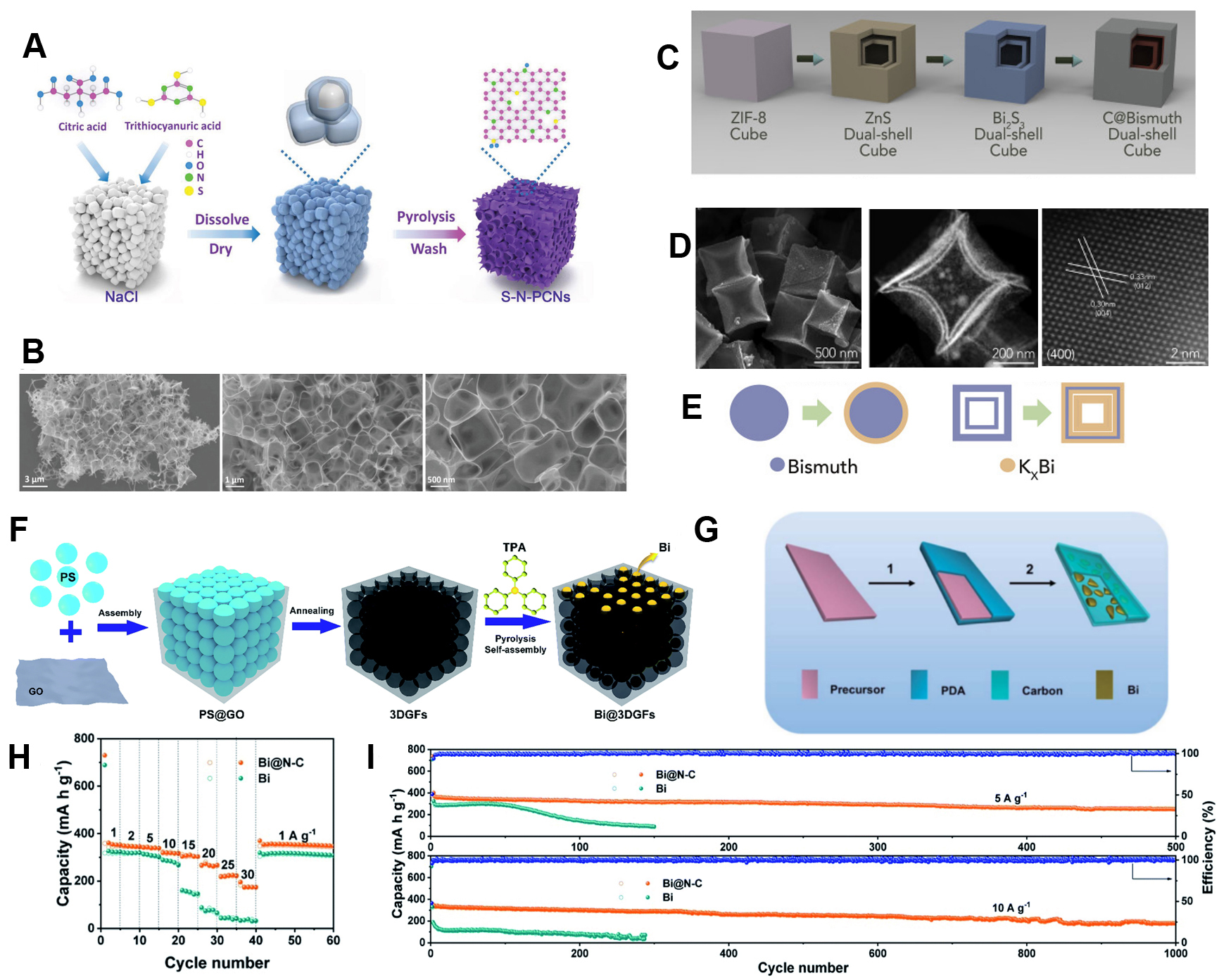

N-doped carbons were demonstrated to simultaneously improve the conductivity and electrochemical activity of carbon materials and were applied in combination with Bi[63,64], as shown in Figure 6A-F. Similarly, Shi et al. designed a multicore-shell Bi-N nanocomposite using a facile self-template method. The anode delivered a stable performance of 266 mAh g-1 after 1000 cycles at 20 A g-1, as shown in

Figure 6. (A) Schematic illustration and (B) TEM images of Bi@porous carbon composite[64]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (C) Schematic illustration of synthetic procedure and (D) TEM images of C@DSBC. (E) Schematic illustration of superior electrochemical performance of C@DSBC under high current density[60]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (F) Schematic illustration of synthesis procedure for Bi@3D graphene foams (GFs)[63]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. (G) Schematic illustration of synthesis of Bi@N-C composite. (H) Rate performance of Bi@N-C and Bi anodes from 1 to 30 A g-1 and (I) long-term cycling stability of Bi@N-C and Bi anodes at high rates of 5 and 10 A g-1[65]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry.

Another important method to improve the electrochemical performance of Bi is nanoengineering. In addition to the multicore-shell structures mentioned above, which are typical designs for Bi-based anodes, Xie et al. designed a dual-shell bismuth box (DSBC) anode[60], which delivered a high-rate capacity of

As reported, K+ ions have lower Lewis acidity than Li+ and Na+ ions, indicating a lower ability to accept electrons from anions and solvents. Thus, potassium salts have a lower degree of dissociation. The salt solubility is based on the Born-Haber cycle:

where

To date, the reported potassium salts used in Bi-based anodes are KPF6 and potassium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (KFSI). KPF6 has a high calculated Kapustinskii lattice energy of 564.9 kJ mol-1, while KFSI has a lower lattice energy[70], indicating that KFSI has higher solubility compared to KFP6. KFSI also has higher ionic conductivity than KPF6 and KFSI-based electrolytes can form more stable SEI layers. This is because the FSI- anion has weak S-F bonds that make it easier to form KF, which is a main component in the SEI layer[71].

Zhang et al. first used KFSI as the electrolyte salt in Bi-based anode materials with ethylene carbonate (EC) and diethyl carbonate (DEC) as solvents[59]. The results indicated that the KFSI-based electrolyte had better cycling performance compared to the KPF6-based electrolyte. The morphological and mechanical properties of the KFSI and KPF6 electrolytes were investigated using atomic force microscopy, Kelvin probe microscopy and TEM. The results demonstrated that the KPF6-based electrolyte formed a thicker and more heterogeneous SEI layer, while the SEI layer in the KFSI-based electrolyte was more uniform.

Ether solvents are the most used solvents for Bi-based anode materials. As discussed above, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels of solvents or anions are lower when solvents or anions modify a cation through coordination. This is because an electron pair is donated to the cation. Thus, an anode with chemical potential μ > Elumo can spontaneously transfer electrons to the LUMO of the electrolyte and trigger reduction. In ether solvents, the HOMO values of the ion-solvent complexes are of the order of Li+ > Na+ > K+, while the LUMO values follow the order of Na+ > K+ > Li+[13]. Therefore, the reduction and oxidation products in ether-based PIBs are complicated. Huang et al. first used dimethoxyethane (DME) as their ether-based solvent in Bi-based PIBs[57]. Using XPS and in-situ Raman spectroscopy to probe the SEI components, it was revealed that C-C(H), C-O, C=O and K-O bonds were formed and the SEI consisted of organic and inorganic compounds, such as

Generally, electrolytes for Bi-based PIBs contain 1 M K salts. Based on recent reports, ~70% of the electrolytes applied in Bi-based PIBs are 1 M K dissolved in DME. Increasing the salt content results in enhanced interactions between cations and anions. Increasing the salt concentration also decreases the content of free-state solvent molecules. When the concentration is increased (>3 M), however, the free molecules decrease, leading to a change in the solution structure, which usually gives rise to extraordinary electrochemical properties and shifts the location of the LUMO from the solvent molecules to the salt. Thus, the reductive decomposition of salts takes place before the decomposition of the solvent, which results in the formation of a stable SEI[69,72]. Zhang et al. first used a concentrated electrolyte in Bi-based PIBs[73]. The Bi@C anode delivered the highest capacity of 202 mAh g-1 in a 5 M KFSI-diethylene glycol dimethyl ether electrolyte, which was higher than those in 1 M (163 mAh g-1), 3 M (153 mAh g-1) and 7 M (93 mAh g-1) electrolytes. Based on this study, the differences in the electrochemical performance were due to the different reduction resistances. The decreased reduction resistance in the 5 M electrolyte depressed the irreversible electrochemical reaction and formed less SEI compared to the less concentrated electrolytes[73]. A comparison of the electrochemical performance of Bi-based anode materials in PIBs is shown in Table 2.

Summary of electrochemical performance of Bi-based anodes for PIBs

| Anode materials | Modification methods | Synthesis method | Redox potential (vs. | Current Density (mA g-1) | Initial capacity (potassiation) (mAh g-1) | Initial depotassiation (mAh g-1) | 1st CE | Cycling performance | Best rate capability | Electrolyte | Ref. | |

| Bi/rGO | Bi/rGO | Hybridized with graphene | Simple room- temperature solution synthesis method | 1.29 V 0.72-0.23 V | 50 | 700 | 441 | 63% | Reversible capacity of 290 mAh g-1 after 50 cycles at current density of 50 mA g-1 | 290 mAh g-1 after 50 cycles at current density of 50 mA g-1 | 1 M KFSI in EC/DEC (1:1, v/v) | [59] |

| Porous Bi | Nanostructural design | Commercial | 0.93-0.30 V | 2C | 371.4 | 322 | 87.2% | After 300 cycles, the capacity remained at 282 mAh g-1 | At 3C, the capacity is still high at up to 321.9 mAh g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in DME. | [58] | |

| Bi@3DGFs | Hybridized with 3D porous graphene/design of 2D nanostructure | Solid-state reaction | 0.4-0.5 V 0.6-0.7 V | 100 | 671 | 241 | 36% | 185.2 mAh g-1 at 10 A g-1 after 2000 cycles | Rate capability of 180 mAh g-1 at 50 A g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in DME | [63] | |

| Bi-doped porous carbon | Hybridized with porous carbon/design of nanostructure | Wet chemistry/thermal treatment | / | 200 | 656 | 382 | 58.2% | High capacity of 107 mAh g-1 at 20 A g-1 | 0.8 M KPF6 in EC/DEC | [64] | ||

| Bi nanorod/ carbon | Hybridized with carbon | Wet chemistry/thermal treatment | 0.2-0.5 V | 1000 | 723 | 470 | 65% | 91% capacity retention at 5 A g-1 after 1000 cycles | 289 mA h g-1 at current density of 6 A g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in DME | [74] | |

| Bi nanorod/ N-doped carbon | Hybridized with carbon/design of nanostructure | Thermal method | 0.3-0.5 V | 385 | 450 | 316 | 70% | 266 mA h g-1 over 1000 cycles at 10C | 297 mA h g-1 at 20C | 1 M KPF6 in DME | [66] | |

| Bi@N-doped carbon nanosheets | Hybridized with N-doped carbon/design of nanostructure | Wet chemistry/thermal treatment | 0.3-0.5 V | 1000 | 721 | 346 | 48% | 180 mAh g-1 at 30 A g-1 after 1000 cycles | 175 mAh g-1 at 30 A g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in DME | [65] | |

| Bi@N-doped carbon | Hybridized with N-doped carbon/design of nanostructure | Evaporation method | 0.25-0.81 V | 50 | 624 | 373 | 59.7% | 179.1 mAh g-1 at 50 mA g-1 after 300 cycles | 162 mA h g-1 at 1.5 A g-1 | 1 M KFSI in DME | [75] | |

| Multicore-shell Bi@N-C | Hybridized with Carbon/design of nanostructure | Solvothermal method/ Thermal treatment | 0.77-0.32 V | 1000 | 972 | 355 | 36.5% | 235 mAh g-1 after 2000 cycles at 10 A g-1 | 152 mAh g-1 at 100 A g-1 | 1 M KPF6 in DME | [76] |

Based on the current study of Bi-based PIBs, KFSI-based electrolytes have better electrochemical performance compared to KPF6-based electrolytes because of the higher ionic conductivity and the formation of a more stable and uniform SEI. Some ether-based electrolytes have extraordinary performance in half cells because their ether-derived SEI possesses better mechanical flexibility. The concentrated electrolyte can improve the electrochemical performance to a certain extent due to the lower resistance of the electrolyte.

Sb-based electrodes for PIBs

Antimony is a layered structure hexagonal element with a high electrical conductivity of 2.5 × 106 S·m-1. Studies of Sb as anode applied in batteries can be traced back to the 1970s[77] when Weppner first studied its kinetic parameters and thermodynamic properties in mixing conducting electrodes to be applied in a Li3Sb system. Theoretically, one mole of Sb can alloy with three moles of lithium, sodium or potassium. The first study of Sb in PIBs was in 2015[78]. Sb is a promising anode material with a high theoretical capacity of

K-ion storage mechanism of Sb

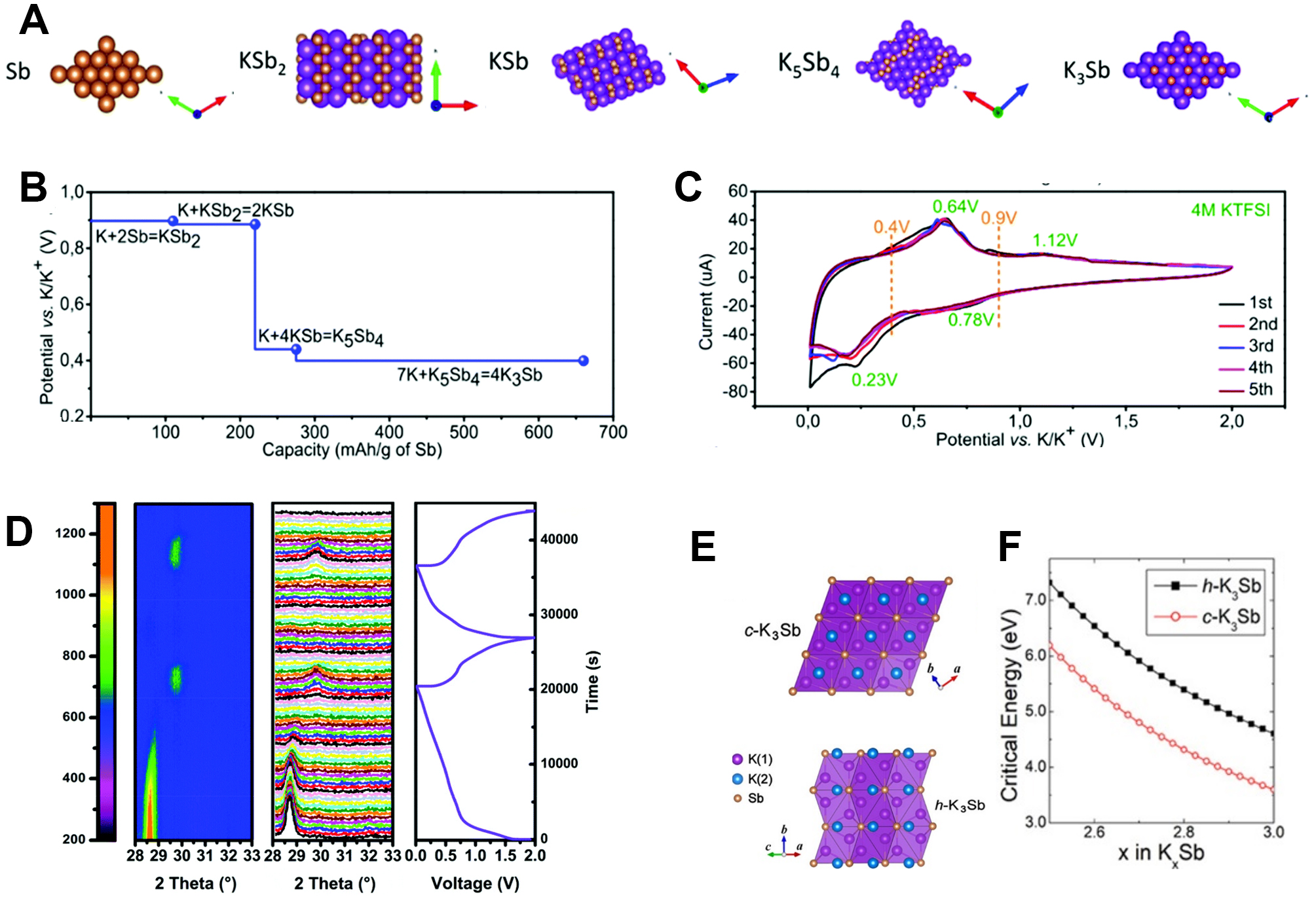

Based on the Sb-K phase diagram, there are four K-Sb binary phases going through K3Sb, K5Sb4, KSb and KSb2 with decreasing K content[79]. The corresponding equilibrium potentials of KSb2, KSb, K5Sb4 and K3Sb are 0.890, 0.849, 0.439 and 0.398 V, respectively, based on DFT computations[74], which are shown in Figure 7A-C. In-situ XRD experiments and cyclic voltammetry (CV) were carried out to analyze the phase changes[80]. In the discharge process, the first step was the transformation of hexagonal Sb to amorphous Sb. As reported, the peak at 28.6° corresponding to the (012) phase of Sb gradually became weaker[81], as shown in Figure 7D. In the amorphous region, KSb2 and KSb phases can form at the potential of 0.78 V and at the potential of 0.23 V, K5Sb4 phase can form based on the CV results. When fully discharged to ~0.2 V, the cubic K3Sb phase with Fm3m symmetry forms as the final potassiation product. Upon charging, the K3Sb phase gradually decreases by the formation of the intermediate phase KxSb. When further charging, the Sb phase forms with the decomposition of intermediate KxSb. In addition, the cubic K3Sb phase can be observed in the second cycle, while no crystalline Sb can be observed[82].

Figure 7. (A) Crystal structures of Sb and K-Sb binary phases. (B) DFT-calculated equilibrium voltages (vs. K/K+) for potassiation process. (C) CV curves of Sb-based electrode at a scan rate of 0.05 mV s-1[80]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. (D) In-situ XRD patterns of 3D Sb nanoparticle (NP)@C electrode during a potassiation/depotassiation/potassiation process at 100 mA g-1 and the corresponding discharge/charge curves[81]. Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry. (E) Crystal structures of c-K3Sb and h-K3Sb. (F) Critical energies for nucleation of K3Sb phase[83]. Copyright 2019, American Chemistry Society.

One interesting observation is the formation of the cubic K3Sb phase as the fully discharged product. There are two polymorphs of K3Sb, hexagonal K3Sb (h-K3Sb) and cubic K3Sb (c-K3Sb). Based on the DFT calculations, h-K3Sb is more stable than c-K3Sb, as shown in Figure 7E[83]. If we consider the crystalline energy and the reaction activation energy, however, the results are different. The following equation represents the activation barrier ΔE*(x):

where γ represents the surface energy, ΔEg represents the energy gain on passing from the crystalline to amorphous phase and V0 is the molar volume of the crystalline phase, as shown in Figure 7E and F. Even the molar energy gain of h-K3Sb is higher than that of c-K3Sb by ~0.12 eV and h-K3Sb also has a higher surface energy and lower density. As a result, h-K3Sb has a higher activation barrier, which results in the final formation of c-K3Sb instead of h-K3Sb[83]. Thus, based on current reports, the reaction can be concluded as Sbcrystal → Sbamorphous, Sbamorphous + xK+ + xe- ↔ KxSbamorphous and KxSbamorphous + (3-x)K+ + (3-x)e- ↔

The study of the potassiation mechanisms of Sb-based alloy compounds has also attracted significant attention. Liu et al. were the first to report the potassiation/depotassiation process of Sb2S3[84]. The process includes three steps. The first step is an intercalation reaction: Sb3S3 + xK+ + xe- → KxSb2S3. The following two steps are the conversion-alloying reaction of Sb2S3 + xK+ + xe- ↔ yK3Sb + zK2S3. Their results showed no interaction process but only an alloying-conversion process with extra electron transfer. Sb2Se3-based microtubes were prepared and analyzed by Yi et al.[85]. Based on their study, the potassium insertion reaction in the composite delivered a conversion-alloying reaction. The reaction process can be concluded to be Sb2Se3 + 12K+ + 12e- ↔ 3K3Sb + 2K2Se3. The Sb2Se3 compound first reacted with potassium to form the K2Se and Sb phases, which were further alloyed with potassium. In the reduction process, K2Se can be observed as an intermediate phase, which is reconverted to form Sb2Se3. The whole process is reversible.

As discussed above, Sb will alloy with K to form the K3Sb phase as the final alloying product, while Sb-based compounds will first undergo a conversion reaction with a subsequent alloying reaction.

Modification strategies for Sb-based anode materials

As discussed above, Sb will form K3Sb as the final product. Sb has a high theoretical capacity of

Nanostructural engineering combined with carbon materials has been a widely practiced method to improve the electrochemical performance of Sb. Huang et al. designed a hybrid structure with Sb nanoparticles as yolk confined in a carbon box shell, which was prepared using metal-organic frameworks as precursors[86]. As observed by in-situ TEM, this hybrid material, which consists of carbon fibers with yolk-shell Sb@C, has structural advantages in the potassiation and depotassiation processes, as shown in Figure 8A-D. The inner Sb nanoparticles suffer from significant volume expansion during the potassiation process, while the void space effectively relieves the volume changes and the carbon fiber shell maintains the integrity of the structure and improves the conductivity. As a result, it delivered a capacity of 227 mAh g-1 after 1000 cycles and had a high Coulombic efficiency of ~100%. Liu et al. designed and constructed Sb nanoparticles confined by carbon, which exhibited long cycling stability over 800 cycles with a capacity retention as high as 72.3%[87], as shown in Figure 8E.

Figure 8. (A) Illustration of TEM device and (B) potassiation/depotassiation processes of Sb@carbon nanofibers (CNFs) with Sb nanoparticles confined in carbon shell. (C and D) Potassiation and depotassiation processes of Sb@CNFs[86]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (E) Schematic illustration of traditional Sb and Sb@graphene (G)@C electrodes during potassiation/depotassiation processes[87]. Copyright 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry.

A variety of porous structures have been applied to hinder the volume change during cycling[88-91]. A microsized nanoporous antimony potassium anode was designed with tunable porosity[88]. The nanoporous structure can accommodate volume expansion and accelerate ion transport. Similarly, Zhao also encapsulated Sb nanoparticles within a porous architecture[89]. The composite delivered a high capacity of 392.2 mAh g-1 at 0.1 A g-1 after 450 cycles. Carbon nanofibers have also been applied as nanochannels to solve the issues of poor potassium-ion diffusion and significant volume variation. The Sb@CNFs delivered a reversible capacity of 225 mAh g-1 after 2000 cycles[90]. Cheng et al. utilized a single-crystal nanowire structure to improve the electrochemical performance of a Sb2S3 anode material[91]. After full potassiation, no obviously pulverization was observed, although the diameter of the as-prepared Sb2S3@C nanowires increased from 83 to 120 nm with a 45% expansion. The overall expansion of Sb2S3@C is ~111%, which is lower than the Sn-K alloying reaction (≈ 197%), indicating that the nanowire structure can effectively hinder the volume change during the potassiation/depotassiation process. Similarly, Jiao and Yu[92,93] also utilized a one-dimensional structure. A 2D structure was also applied to improve the electrochemical performance of Sb-based anode materials. Wang et al. designed a Sb2S3 nanoflower/MXene composite that exhibited a high reversible capacity of 461 mAh g-1 at a current density of 100 mA g-1[94]. Its structural stability was enhanced by the strong interfacial connection between Sb2S3 and the matrix. A 3D structure was also applied in Sb-based anode materials. A core-shell Sb@Sb2O3 heterostructure was fabricated, which delivered an excellent capacity of 239 mAh g-1 at 5 A g-1 in PIBs[95]. These methods efficiently improved the electrochemical performance of Sb-based anode materials.

Another important method is improving the binder for the electrodes. He et al. used a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) binder, which has a high capacity of 226 mAh g-1 over 400 cycles[96]. Compared to PVDF, sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) can improve the initial columbic efficiency due to the pre-formed SEI. In addition to these traditional binders applied in PIBs, the group of Guo developed a CMC-polyacrylic acid (PAA) binder for a Sb-based composite[97]. The cycling performance of the CMC-PAA binder was improved due to the condensation reaction between the hydroxyl groups of CMC and the carboxylic acid moieties of PAA, which effectively increased the viscoelastic properties of the binder and increased the mechanism properties of the electrodes.

In summary, the modification methods for Sb-based anode materials are mainly nanostructural engineering by designing nanofibers, nanoflowers, box shell structures and nanoporous structures in combination with carbon fibers, MXenes, carbon shells, and so on. Multistructural design efficiently hinders the significant volume change and efficiently alleviates the structural degradation.

Ge-based anode materials

Ge has a diamond cubic crystal structure, which is the same as silicon, and it is in the IVA group. Germanium is an attractive non-toxic alloy-based anode material. The original study of Ge-based anode materials can be dated back to the 1980s when the formation of the Ge-Li binary was first discovered.

Mechanism of Ge-based anodes in PIBs

Ge has a high capacity of 1623 or 1384 mAh g-1 by the formation of the lithium-rich compounds Li55Ge5 and Li15Ge4, respectively[98-102], which makes it a promising anode material in LIBs. In SIBs, germanium delivers a high capacity of 389 mAh g-1 by forming the binary compound NaGe[103-106] at a voltage plateau of

Modification strategies for Ge-based anode materials

Compared to other alloy-based anode materials, germanium has a relatively lower theoretical capacity. It experiences a limited volume change during ion insertion and extraction processes; however, compared to other alloy-based anodes, which amount to ~272% in LIBs and 120% in SIBs. Similarly, Ge undergoes a significant volume change in the discharge/charge process in PIBs. Although the volume changes of germanium are less compared to other alloy-based materials, they can cause pulverization and result in a capacity decrease in the same manner.

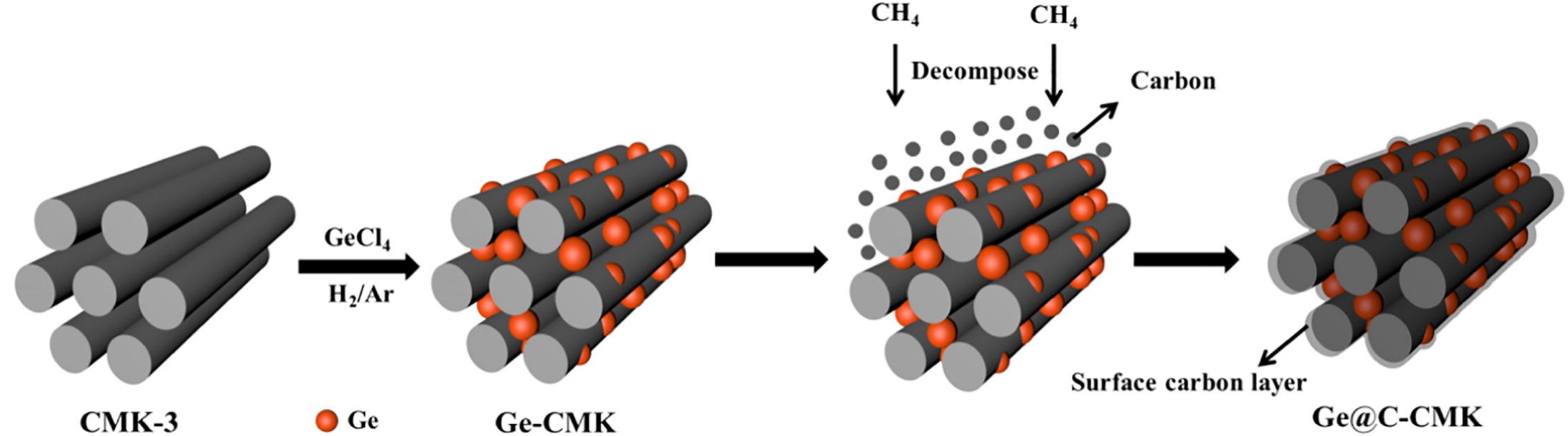

In order to improve the electrochemical performance of germanium-based anode materials, the ordinary methods include constructing nanostructures combining Ge with carbon materials[110-114] in LIBs and SIBs. Li et al. designed hollow carbon spheres with germanium encapsulated inside by introducing a germanium precursor into the hollow carbon particles and then followed this with a thermal reduction[114]. The hollow carbon spheres served as a physical matrix that could effectively protect the germanium core from coalescing or pulverization. Similarly, Mo et al. designed a 3D-interconnected porous graphene foam with germanium quantum dots doped into it by a facile approach[112]. This structure provided close contact between the electrode materials and the current collector, and the yolk-shell structure effectively alleviated the significant volume changes and provided a stable SEI. Designing nanostructures in combination with carbon materials are also an efficient method to improve the electrochemical performance of Ge-based materials in PIBs. Liu et al. synthesized a dual carbon structure with germanium encapsulated inside[106]. The as-prepared dual carbon matrix was composed of mesoporous carbon and an amorphous carbon layer, as shown in Figure 9. Using this structure, the dual carbon effectively alleviated the expansion of germanium. Yang et al. designed a nanoporous structure Ge with small ligaments and interconnected porous prepared by a chemical-dealloying method[107]. The nanoporous germanium delivered a high initial capacity of

Figure 9. Schematic illustration of preparation of Ge-CMK and Ge@C-CMK composites[106]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

Using active or inactive elements to form Ge-based binaries or composites is another effective method to improve the electrochemical performance. The inactive metals alloyed with Ge include Co[115] and Cu[116], which can improve the conductivity. The active materials have been applied in the formation of Ge-based compounds are Si[117], Sn[118], Sb[119], Te[120] and Se[121], which have high theoretical capacities. As discussed above, phosphorus has the highest theoretical capacity in PIBs and can increase the capacity of the total capacity by the formation of GePx. Zhang et al. prepared GeP5, which delivered a stable capacity of

Sn-based anode materials for PIBs

Sn has been an attractive anode material for LIBs and SIBs for a long time and has high theoretical capacities of 991 and 845 mAh g-1 via the formation of Li4.4Sn and Na15Sn4, respectively. The study of Sn in PIBs started in 2016[123], with the formation of KSn. Sn has a theoretical capacity of 226 mAh g-1 in PIBs.

Mechanism of Sn-based anode materials

Based on the K-Sn phase diagram, K2Sn, KSn, K2Sn3, KSn2 and K4Sn23 can form at different temperatures. Wang et al. were the first to study the reaction mechanism of Sn in PIBs using in-situ TEM and XRD methods[124]. They revealed a two-step process corresponding to Sn → amorphous K4Sn9 → KSn. A similar potassiation process was evaluate, as shown in Figure 10A-C. The results revealed that the tetragonal K4Sn4 phase was formed at a voltage of ~0.01 V. Their study indicated that K4Sn4 and KSn are overall identical phases in terms of their crystal structure. In the de-alloying process, K4Sn4 decomposed at 0.98 V[125].

Figure 10. (A) Synchrotron XRD data obtained in situ during (B) CV scans of 1 μm-thick Sn film electrode in K half-cell and (C) zoomed-in in-situ XRD patterns corresponding to region associated with phase transformation of primary interest during electrochemical potassiation of Sn[125]. Copyright 2017, Electrochemical Society. (D) In-situ XRD results for hierarchical polyaspartic acid-modified SnS2 nanosheets embedded into hollow N-doped carbon fibers (PASP@SnS2@CN) electrode at different charge/discharge states[126]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (E) Schematic illustration of potassiation/depotassiation process in SnSe@C nanocomposite[128]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier Ltd.

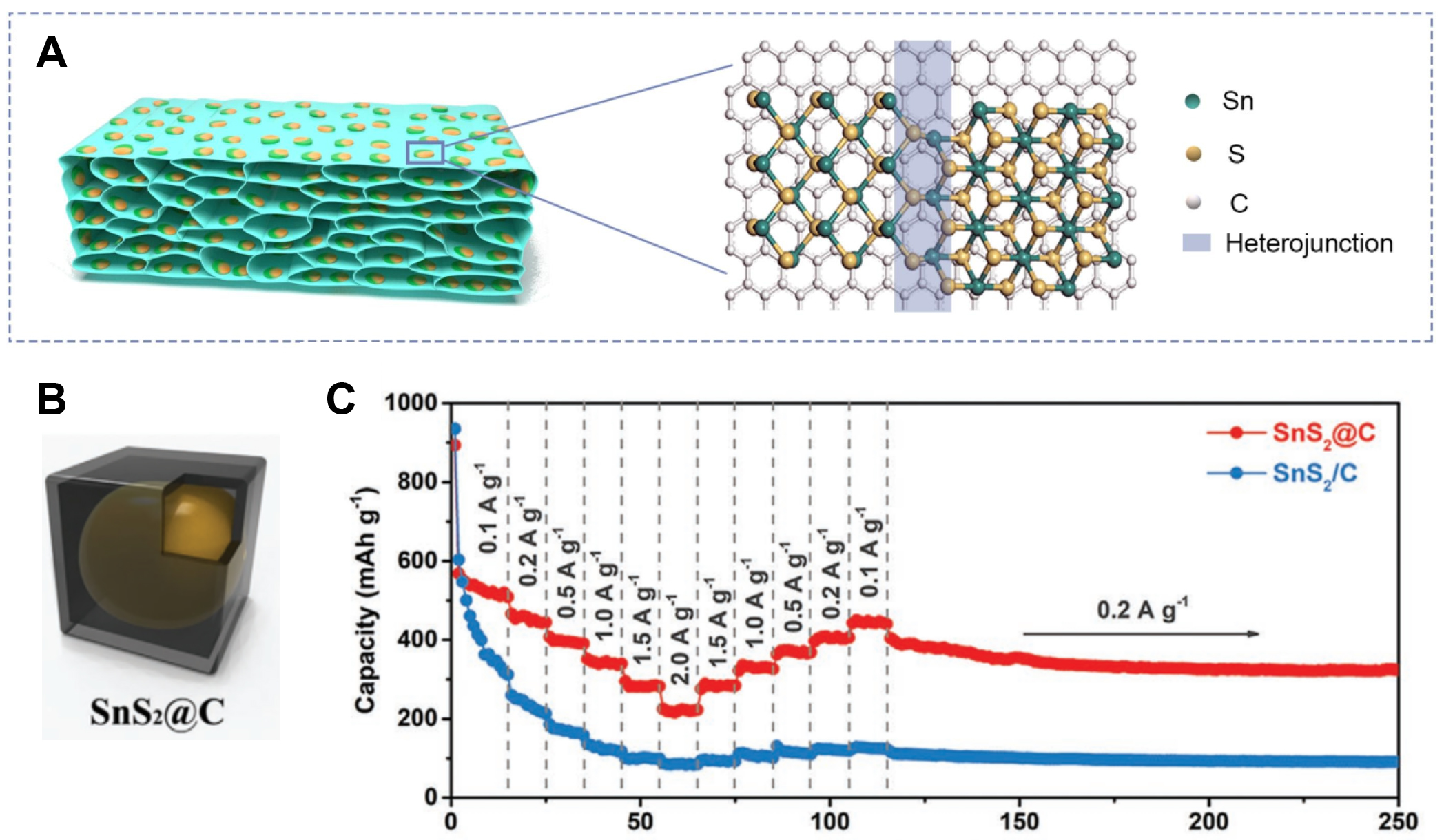

The study of the mechanism of Sn-based alloys has also attracted significant attention. The teams of Ma and Ci have both studied the potassium-ion storage mechanism in SnS2[126,127] and their results are similar. In the discharge process, SnS2 → SnS + K2S5 → Sn + K2S5 + K4Sn23 → K2S5 + KSn, as shown in Figure 10D. Like the alloying process of crystalline Sn in PIBs, the final product, KSn phase, is formed within the voltage range of 0.20-0.01 V. For SnSe, based on the study of Verma et al., the potassiation process is SnSe → Sn + K2Se5 →

Modification strategies for Sn-based anode materials

Sn-based alloys suffer from significant volume expansion in PIBs, which results in pulverization and capacity drop. Various methods have been applied to ameliorate the volume change and improve the electrochemical performance. To solve these drawbacks, hierarchical nanostructural design is an effective strategy. 2D nanosheet structures have been applied to improve the electrochemical performance of Sn-based anode materials. Lakshimi et al. studied an SnS2/graphene composite in PIBs, which delivered a high capacity of 350 mAh g-1[129]. Qin et al. designed hierarchical polyaspartic acid-modified SnS2 nanosheets embedded into carbon[126]. The as-prepared electrode enlarged the interlamellar space of 6.8 Å and delivered a high-rate performance of 273 mAh g-1 at a current density of 2 A g-1[126]. Cao et al. also designed a 2D SnS nanosheet composite that exhibited an ultralong lifespan[130]. Sun et al. used a nanosheet structure with strong interactions between the layers, which can efficiently accelerate electron and ion transfer and hinder the volume change[131]. The as-prepared composite delivered a stable long-term cycling performance of

The group of Yang also designed a nanosheet structure, which delivered a high capacity of 206.1 mAh g-1 after 800 cycles[132]. Zhou et al. designed a sheet-like tin sulfide composite, as shown in Figure 11A, which delivered a rapid rate capacity of 460 mAh g-1 at a current density of 2A g1 and an excellent cycling stability of over 500 cycles at a current density of 1 A g-1[133]. The utilization of the 2D structure efficiently hinders the volume change and improves the electronic and ionic conductivity. Combining Sb-based alloys with 3D structures has been an effective method to improve the electrochemical performance of PIBs. Yolk-shell 3D carbon boxes were designed as a matrix to accommodate SnS2, as shown in Figure 11B. Introducing interior void space has been an effective strategy to accommodate the volume changes. The composite delivered a stable cycling performance of 352 mAh g-1 at 1 A g-1, as shown in Figure 11C[134].

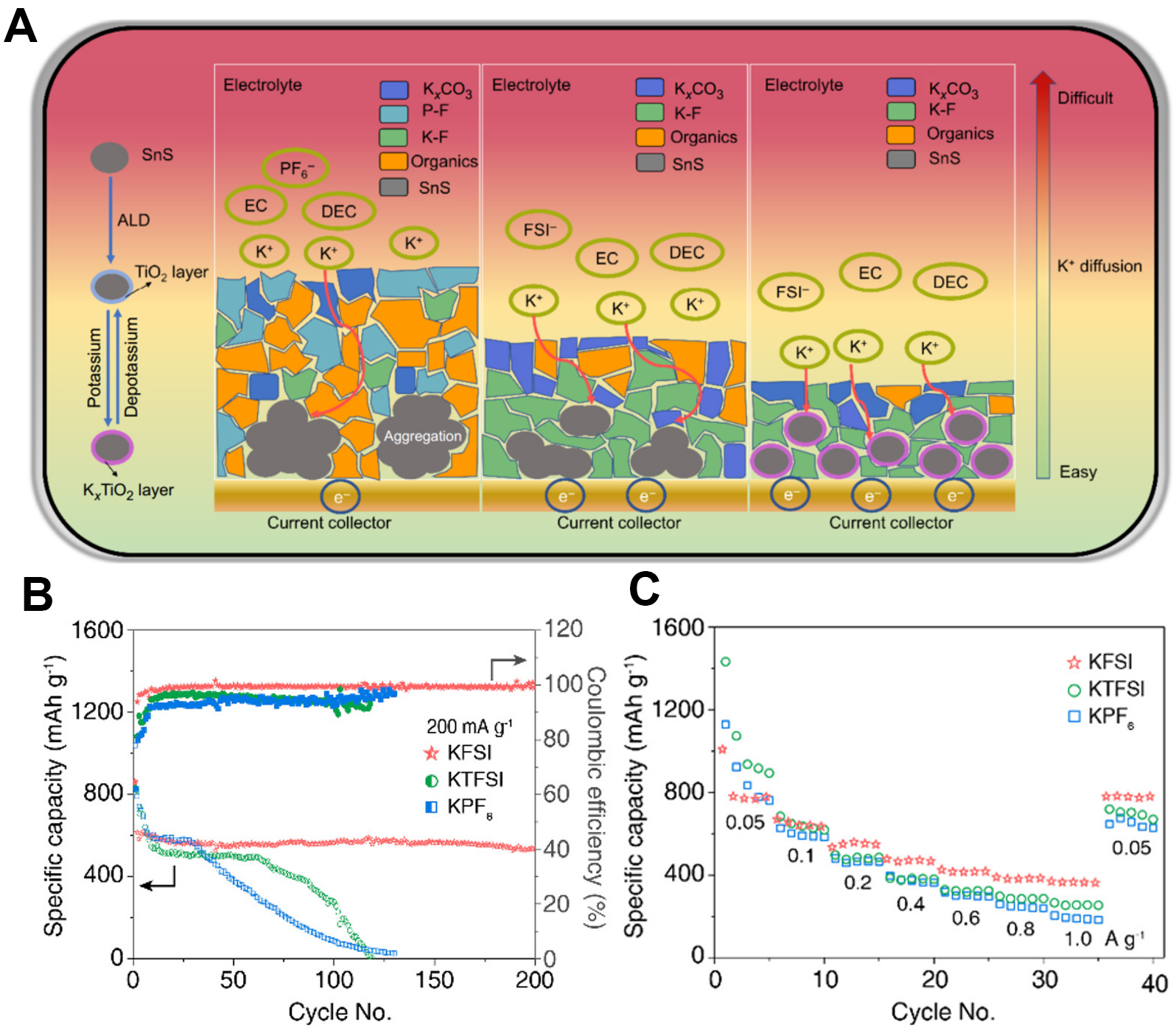

Another alternative method to enhance electrochemical performance is using the proper salt to form a robust SEI. Compared KFSI and KPF6 with the same solvent. The results indicated that the Sn-based composite in the KFSI-based electrolyte exhibited a highly stable cycling performance of 450 mAh g-1 over 400 cycles. The KFSI salt in an ethylene carbonate/diethyl carbonate solvent more easily forms a K-F-rich inorganic SEI due to the critical role of FSI-1 anions, which can inhibit the decomposition of the electrolyte[135], as shown in Figure 12A. Similarly, the group of Chen also studied the different salts in electrolytes resulting in the differences in SEI formations. Their results indicated that batteries with KFSI featured better performance than those with KTFSI and KPF6. The composition of the SEI formed in the KFSI-based electrolyte is mainly K-F, which can effectively enhance the mechanical properties of the SEI. The SEI from the KFSI-based electrolyte also stops growing after 20 cycles, while the SEIs of the KTFSI and KPF6-based electrolytes continue to grow thicker, thereby hindering the potassium-ion transportation, as shown in Figure 12B and C[136]. Sn has a high theoretical capacity of 226 mAh g-1 in PIBs, with the formation of KSn as the final product. The challenge facing Sn-based alloy anode materials in PIBs is their significant volume change and pulverization. In order to hinder the volume change of Sn-based alloys, modification methods have been applied. The design of 2D nanosheets, 3D nanoboxes and SEIs has been applied in the modification and has efficiently improved the electrochemical performance.

Figure 12. (A) Schematic illustration of chemical composition and ionic transport of electrode/electrolyte interface[135]. Copyright 2021, Springer Nature. (B) Capacity retention of SnS2/N-rGO composite electrodes in EC/DEC electrolytes with various K+ salts at a current density of 200 mA g-1. (C) Rate capability of cells with various K+ salts at current densities from 0.05 to 1 A g-1[136]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

SUMMARY AND OUTLOOK

Their low cost and the natural abundance of their raw materials make PIBs promising next-generation energy storage devices. The large radius of the potassium ion results, however, in slower ion transport and limited cycling life. Recently, significant research has been completed on PIBs, but one of the major challenges is to develop high-performing anodes.

This review summarizes the recent research progress on alloy-type anodes for PIBs, including P-, Bi-, Sb-, Ge- and Sn-based compounds and composites. Alloy-based anode materials undergo alloy conversion reactions in which the material finally reacts with K to form KxM. Therefore, alloy-based materials have high theoretical capacities of 2596, 385, 687, 369 and 226 mAh g-1, respectively, and volumetric capacities of 4750, 3752, 4596, 1964 and 1653 mAh cm-3 make them high potential anode materials for PIBs. The mechanisms of the potassiation and depotassiation processes have been deeply discussed and analyzed. For an elementary substance, the mechanism is a simple alloying reaction. For compound materials, the reaction process is mainly a conversion-alloying reaction. The various formations of the intermediate product in the potassium ion for the same material are mainly due to the various nanostructures and grain sizes of the materials. Modifications of the materials have also been explored and investigated. The approaches can be classified as the hybridization of active materials with high conductivity and architectural engineering. Highly conductive materials, including graphene, carbon nanotubes, graphite, N-doped carbon and carbon nanosheets. The architectural engineering methods, including the design of one-dimensional nanotubes, 2D nanosheets and 3D structural materials, such as core-shell structures and their combinations. By using these modification methods, the significant volume change and sluggish reaction kinetics can be effectively solved.

The electrochemical performance of alloy-based electrodes has now been greatly improved and the reaction processes have also been deeply analyzed. Further research can be carried out on the following aspects:

(1) Low initial Coulombic efficiency is the main problem that remains for anode materials, which might be ascribed to the irreversible insertion of potassium ions and the decomposition of the electrolyte. In the full cell, the maximum cell energy is obtained when the anode irreversible capacity exactly matches that of the cathode material. The low initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) indicates the large consumption of K+ provided from cathode, which results in lower energy density in the full cell and faster capacity drop. Improving electrolytes with higher ion conductivity will increase the ICE.

(2) Although fabricated nanostructures and hybrids with carbon will significantly hinder the volume changes, alloy-based anode materials still face the problem of volume expansion and pulverization during cycling. Furthermore, this problem may bring the severe side effect of the reaction between the electrolyte and the new surface of the electrode, leading to the formation of the SEI on the new surface, which results in a capacity decrease and instability of the cycling performance. This side effect may also result in the maldistribution of electrons, leading to dendrite growth and the polarization of electrodes. This will limit the application and manufacturing of PIBs. Electrolyte and electrode interface engineering or controlling the content and structure of the SEI layer or designing an artificial SEI layer can make up for the shortage.

(3) Safety problems are still an issue for future development. Alloy-based anode materials are currently limited in their application at high and low temperatures. Aqueous electrolyte and flame-retardant electrolyte systems could be promising designs for future applications. In addition, non-flammable carbonate electrolytes can also be used to address battery safety issues.

In light of the abundance of potassium resources and the significant progress that has been made in the research on alloy-based anodes for PIBs, these anodes will be promising for commercialization in the near future.

DECLARATIONS

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank Dr. Tania Silver for her critical reading of the manuscript.

Authors’ contributionsCharacterizing, writing original draft: Yang Q

Review, and supervision: Chou S, Liu H, Wang J

Editing: Fan Q, Peng J

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work is financially supported by Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Project (DP180101453).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2023.

REFERENCES

1. Scott V, Haszeldine RS, Tett SFB, Oschlies A. Fossil fuels in a trillion tonne world. Nat Clim Chang 2015;5:419-23.

2. Mohr S, Wang J, Ellem G, Ward J, Giurco D. Projection of world fossil fuels by country. Fuel 2015;141:120-35.

3. Abas N, Kalair A, Khan N. Review of fossil fuels and future energy technologies. Futures 2015;69:31-49.

4. Höök M, Tang X. Depletion of fossil fuels and anthropogenic climate change - A review. Energy Policy 2013;52:797-809.

6. Berner RA. The long-term carbon cycle, fossil fuels and atmospheric composition. Nature 2003;426:323-6.

7. Gustavsson L, Börjesson P, Johansson B, Svenningsson P. Reducing CO2 emissions by substituting biomass for fossil fuels. Energy 1995;20:1097-113.

9. Barbir F, Veziroǧlu T, Plass H. Environmental damage due to fossil fuels use. Int J Hydrog Energy 1990;15:739-49.

10. Hameer S, van Niekerk JL. A review of large-scale electrical energy storage: this paper gives a broad overview of the plethora of energy storage. Int J Energy Res 2015;39:1179-95.

11. Castillo A, Gayme DF. Grid-scale energy storage applications in renewable energy integration: a survey. Energy Convers Manag 2014;87:885-94.

12. Etacheri V, Marom R, Elazari R, Salitra G, Aurbach D. Challenges in the development of advanced Li-ion batteries: a review. Energy Environ Sci 2011;4:3243.

13. Hosaka T, Kubota K, Hameed AS, Komaba S. Research development on K-ion batteries. Chem Rev 2020;120:6358-466.

14. Kim H, Kim JC, Bianchini M, Seo D, Rodriguez-garcia J, Ceder G. Recent progress and perspective in electrode materials for K-ion batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2018;8:1702384.

15. Hwang J, Myung S, Sun Y. Recent progress in rechargeable potassium batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2018;28:1802938.

16. Anoopkumar V, John B, Mercy T. Potassium-ion batteries: key to future large-scale energy storage? ACS Appl Energy Mater 2020;3:9478-92.

17. Zhang W, Liu Y, Guo Z. Approaching high-performance potassium-ion batteries via advanced design strategies and engineering. Sci Adv 2019;5:eaav7412.

18. Li W, Bi Z, Zhang W, et al. Advanced cathodes for potassium-ion batteries with layered transition metal oxides: a review. J Mater Chem A 2021;9:8221-47.

19. Zhang X, Wei Z, Dinh KN, et al. Layered oxide cathode for potassium-ion battery: recent progress and prospective. Small 2020;16:e2002700.

20. Eftekhari A. Potassium secondary cell based on Prussian blue cathode. J Power Sources 2004;126:221-8.

21. Li L, Hu Z, Liu Q, Wang J, Guo Z, Liu H. Cathode materials for high-performance potassium-ion batteries. Cell Rep Phys Sci 2021;2:100657.

22. Li L, Hu Z, Lu Y, et al. A low-strain potassium-rich prussian blue analogue cathode for high power potassium-ion batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2021;60:13050-6.

23. Qin M, Ren W, Meng J, et al. Realizing superior prussian blue positive electrode for potassium storage via ultrathin nanosheet assembly. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2019;7:11564-70.

24. Liu S, Kang L, Jun SC. Challenges and strategies toward cathode materials for rechargeable potassium-ion batteries. Adv Mater 2021;33:e2004689.

25. Yang Y, Zhou J, Wang L, et al. Prussian blue and its analogues as cathode materials for Na-, K-, Mg-, Ca-, Zn- and Al-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2022;99:107424.

26. Min X, Xiao J, Fang M, et al. Potassium-ion batteries: outlook on present and future technologies. Energy Environ Sci 2021;14:2186-243.

27. Zhang K, Gu Z, Ang EH, et al. Advanced polyanionic electrode materials for potassium-ion batteries: Progresses, challenges and application prospects. Mater Today 2022;54:189-201.

29. Luo W, Wan J, Ozdemir B, et al. Potassium ion batteries with graphitic materials. Nano Lett 2015;15:7671-7.

30. Zhan F, Wang H, He Q, et al. Metal-organic frameworks and their derivatives for metal-ion (Li, Na, K and Zn) hybrid capacitors. Chem Sci 2022;13:11981-2015.

31. Liu S, Kang L, Zhang J, Jung E, Lee S, Jun SC. Structural engineering and surface modification of MOF-derived cobalt-based hybrid nanosheets for flexible solid-state supercapacitors. Energy Stor Mater 2020;32:167-77.

32. Tu J, Tong H, Zeng X, et al. Modification of porous N-doped carbon with sulfonic acid toward high-ICE/capacity anode material for potassium-ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2022;32:2204991.

33. Tian S, Zhang Y, Yang C, Tie S, Nan J. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheet coated multilayer graphite as stabilized anode material of potassium-ion batteries with high performances. Electrochim Acta 2021;380:138254.

34. Sultana I, Rahman MM, Chen Y, Glushenkov AM. Potassium-ion battery anode materials operating through the alloying-dealloying reaction mechanism. Adv Funct Mater 2018;28:1703857.

35. Komaba S, Hasegawa T, Dahbi M, Kubota K. Potassium intercalation into graphite to realize high-voltage/high-power potassium-ion batteries and potassium-ion capacitors. Electrochem Commun 2015;60:172-5.

36. Cao K, Liu H, Li W, et al. CuO nanoplates for high-performance potassium-ion batteries. Small 2019;15:e1901775.

37. Sultana I, Rahman MM, Ramireddy T, Chen Y, Glushenkov AM. High capacity potassium-ion battery anodes based on black phosphorus. J Mater Chem A 2017;5:23506-12.

38. Jin H, Wang H, Qi Z, et al. A black phosphorus-graphite composite anode for Li-/Na-/K-ion batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020;59:2318-22.

39. Xiong P, Bai P, Tu S, et al. Red phosphorus nanoparticle@3D interconnected carbon nanosheet framework composite for potassium-ion battery anodes. Small 2018;14:e1802140.

40. Wu Y, Hu S, Xu R, et al. Boosting potassium-ion battery performance by encapsulating red phosphorus in free-standing nitrogen-doped porous hollow carbon nanofibers. Nano Lett 2019;19:1351-8.

41. Liu D, Huang X, Qu D, et al. Confined phosphorus in carbon nanotube-backboned mesoporous carbon as superior anode material for sodium/potassium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2018;52:1-10.

42. Zhang W, Mao J, Li S, Chen Z, Guo Z. Phosphorus-based alloy materials for advanced potassium-ion battery anode. J Am Chem Soc 2017;139:3316-9.

43. Zhang W, Wu Z, Zhang J, et al. Unraveling the effect of salt chemistry on long-durability high-phosphorus-concentration anode for potassium ion batteries. Nano Energy 2018;53:967-74.

44. Li B, He Z, Zhao J, Liu W, Feng Y, Song J. Advanced Se3P4@C anode with exceptional cycling life for high performance potassium-ion batteries. Small 2020;16:e1906595.

45. Yang Q, Tai Z, Xia Q, et al. Copper phosphide as a promising anode material for potassium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2021;9:8378-85.

46. Xu GL, Chen Z, Zhong GM, et al. Nanostructured black phosphorus/ketjenblack-multiwalled carbon nanotubes composite as high performance anode material for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Lett 2016;16:3955-65.

47. Yang W, Lu Y, Zhao C, Liu H. First-principles study of black phosphorus as anode material for rechargeable potassium-ion batteries. Electron Mater Lett 2020;16:89-98.

48. Yuan D, Cheng J, Qu G, et al. Amorphous red phosphorous embedded in carbon nanotubes scaffold as promising anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J Power Sources 2016;301:131-7.

49. Ramireddy T, Xing T, Rahman MM, et al. Phosphorus-carbon nanocomposite anodes for lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2015;3:5572-84.

50. Verma R, Didwal PN, Ki HS, Cao G, Park CJ. SnP3/Carbon nanocomposite as an anode material for potassium-ion batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019;11:26976-84.

51. Zhang Z, Wu C, Chen Z, et al. Spatially confined synthesis of a flexible and hierarchically porous three-dimensional graphene/FeP hollow nanosphere composite anode for highly efficient and ultrastable potassium ion storage. J Mater Chem A 2020;8:3369-78.

52. Yang F, Gao H, Hao J, et al. Yolk-shell structured FeP@C nanoboxes as advanced anode materials for rechargeable lithium-/potassium-ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2019;29:1808291.

53. Yang F, Hao J, Long J, et al. Achieving high-performance metal phosphide anode for potassium ion batteries via concentrated electrolyte chemistry. Adv Energy Mater 2021;11:2003346.

54. Liu Q, Hu Z, Liang Y, et al. Facile synthesis of hierarchical hollow CoP@C composites with superior performance for sodium and potassium storage. Angew Chem 2020;132:5197-202.

55. Li D, Zhang Y, Sun Q, et al. Hierarchically porous carbon supported Sn4P3 as a superior anode material for potassium-ion batteries. Energy Stor Mater 2019;23:367-74.

56. Zhang W, Pang WK, Sencadas V, Guo Z. Understanding high-energy-density Sn4P3 anodes for potassium-ion batteries. Joule 2018;2:1534-47.

57. Huang J, Lin X, Tan H, Zhang B. Bismuth microparticles as advanced anodes for potassium-ion battery. Adv Energy Mater 2018;8:1703496.

58. Lei K, Wang C, Liu L, et al. A porous network of bismuth used as the anode material for high-energy-density potassium-ion batteries. Angew Chem 2018;130:4777-81.

59. Zhang Q, Mao J, Pang WK, et al. Boosting the potassium storage performance of alloy-based anode materials via electrolyte salt chemistry. Adv Energy Mater 2018;8:1703288.

60. Xie F, Zhang L, Chen B, et al. Revealing the origin of improved reversible capacity of dual-shell bismuth boxes anode for potassium-ion batteries. Matter 2019;1:1681-93.

61. Shen C, Song G, Zhu X, et al. An in-depth study of heteroatom boosted anode for potassium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2020;78:105294.

62. Chen K, Chong S, Yuan L, Yang Y, Tuan H. Conversion-alloying dual mechanism anode: Nitrogen-doped carbon-coated Bi2Se3 wrapped with graphene for superior potassium-ion storage. Energy Stor Mater 2021;39:239-49.

63. Cheng X, Li D, Wu Y, Xu R, Yu Y. Bismuth nanospheres embedded in three-dimensional (3D) porous graphene frameworks as high performance anodes for sodium- and potassium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:4913-21.

64. Hu X, Liu Y, Chen J, Yi L, Zhan H, Wen Z. Fast redox kinetics in Bi-heteroatom doped 3D porous carbon nanosheets for high-performance hybrid potassium-ion battery capacitors. Adv Energy Mater 2019;9:1901533.

65. Shi X, Zhang J, Yao Q, et al. A self-template approach to synthesize multicore-shell Bi@N-doped carbon nanosheets with interior void space for high-rate and ultrastable potassium storage. J Mater Chem A 2020;8:8002-9.

66. Li H, Zhao C, Yin Y, et al. N-doped carbon coated bismuth nanorods with a hollow structure as an anode for superior-performance potassium-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2020;12:4309-13.

67. Hussain N, Liang T, Zhang Q, et al. Ultrathin Bi nanosheets with superior photoluminescence. Small 2017;13:1701349.

68. Zhou, J, Chen, J, Chen, M, et al. Few-layer bismuthene with anisotropic expansion for high-areal-capacity sodium-ion batteries. Adv Mater 2019;31:e1807874.

69. Hagiwara R, Tamaki K, Kubota K, Goto T, Nohira T. Thermal properties of mixed alkali bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)amides. J Chem Eng Data 2008;53:355-8.

71. Shen C, Cheng T, Liu C, et al. Bismuthene from sonoelectrochemistry as a superior anode for potassium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2020;8:453-60.

72. Hosaka T, Kubota K, Kojima H, Komaba S. Highly concentrated electrolyte solutions for 4 V class potassium-ion batteries. Chem Commun 2018;54:8387-90.

73. Zhang R, Bao J, Wang Y, Sun CF. Concentrated electrolytes stabilize bismuth-potassium batteries. Chem Sci 2018;9:6193-8.

74. Jiao T, Wu S, Cheng J, et al. Bismuth nanorod networks confined in a robust carbon matrix as long-cycling and high-rate potassium-ion battery anodes. J Mater Chem A 2020;8:8440-6.

75. Xiang X, Liu D, Zhu X, et al. Evaporation-induced formation of hollow bismuth@N-doped carbon nanorods for enhanced electrochemical potassium storage. Appl Surf Sci 2020;514:145947.

76. Yang H, Xu R, Yao Y, Ye S, Zhou X, Yu Y. Multicore-shell Bi@N-doped carbon nanospheres for high power density and long cycle life sodium- and potassium-ion anodes. Adv Funct Mater 2019;29:1809195.

77. Weppner W, Huggins RA. Determination of the kinetic parameters of mixed-conducting electrodes and application to the system Li3Sb. J Electrochem Soc 1977;124:1569-77.

78. McCulloch WD, Ren X, Yu M, Huang Z, Wu Y. Potassium-ion oxygen battery based on a high capacity antimony anode. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2015;7:26158-66.

79. Liu Y, Xu J, Kang Z, Wang J. Thermodynamic descriptions and phase diagrams for Sb-Na and Sb-K binary systems. Thermochim Acta 2013;569:119-26.

80. Zheng J, Yang Y, Fan X, et al. Extremely stable antimony-carbon composite anodes for potassium-ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2019;12:615-23.

81. Han C, Han K, Wang X, et al. Three-dimensional carbon network confined antimony nanoparticle anodes for high-capacity K-ion batteries. Nanoscale 2018;10:6820-6.

82. Yi Z, Lin N, Zhang W, Wang W, Zhu Y, Qian Y. Preparation of Sb nanoparticles in molten salt and their potassium storage performance and mechanism. Nanoscale 2018;10:13236-41.

83. Ko YN, Choi SH, Kim H, Kim HJ. One-pot formation of Sb-carbon microspheres with graphene sheets: potassium-ion storage properties and discharge mechanisms. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019;11:27973-81.

84. Liu Y, Tai Z, Zhang J, et al. Boosting potassium-ion batteries by few-layered composite anodes prepared via solution-triggered one-step shear exfoliation. Nat Commun 2018;9:3645.

85. Yi Z, Qian Y, Tian J, Shen K, Lin N, Qian Y. Self-templating growth of Sb2Se3@C microtube: a convention-alloying-type anode material for enhanced K-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:12283-91.

86. Huang H, Wang J, Yang X, et al. Unveiling the advances of nanostructure design for alloy-type potassium-ion battery anodes via in situ TEM. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020;59:14504-10.

87. Liu Q, Fan L, Ma R, et al. Super long-life potassium-ion batteries based on an antimony@carbon composite anode. Chem Commun 2018;54:11773-6.

88. An Y, Tian Y, Ci L, Xiong S, Feng J, Qian Y. Micron-sized nanoporous antimony with tunable porosity for high-performance potassium-ion batteries. ACS Nano 2018;12:12932-40.

89. Wang Z, Dong K, Wang D, et al. A nanosized SnSb alloy confined in N-doped 3D porous carbon coupled with ether-based electrolytes toward high-performance potassium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:14309-18.

90. Ge X, Liu S, Qiao M, et al. Enabling superior electrochemical properties for highly efficient potassium storage by impregnating ultrafine Sb nanocrystals within nanochannel-containing carbon nanofibers. Angew Chem Int Ed 2019;58:14578-83.

91. Cheng Y, Yao Z, Zhang Q, et al. In situ atomic-scale observation of reversible potassium storage in Sb2S3@Carbon nanowire anodes. Adv Funct Mater 2020;30:2005417.

92. Liu H, He Y, Cao K, et al. Stimulating the reversibility of Sb2S3 Anode for high-performance potassium-ion batteries. Small 2021;17:e2008133.

93. Sheng B, Wang L, Huang H, et al. Boosting potassium storage by integration advantageous of defect engineering and spatial confinement: a case study of Sb2S3. Small 2020;16:e2005272.

94. Wang T, Shen D, Liu H, Chen H, Liu Q, Lu B. A Sb2S3 nanoflower/MXene composite as an anode for potassium-ion batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020;12:57907-15.

95. Chen B, Yang L, Bai X, et al. Heterostructure Engineering of Core-Shelled Sb@ Sb2S3 encapsulated in 3D N-doped carbon hollow-spheres for superior sodium/potassium storage. Small 2021;17:e2006824.

96. He X, Liao J, Wang S, et al. From nanomelting to nanobeads: nanostructured SbxBi1-x alloys anchored in three-dimensional carbon frameworks as a high-performance anode for potassium-ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2019;7:27041-7.

97. Wu J, Zhang Q, Liu S, et al. Synergy of binders and electrolytes in enabling microsized alloy anodes for high performance potassium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2020;77:105118.

98. Liang S, Cheng Y, Zhu J, Xia Y, Müller-buschbaum P. A chronicle review of nonsilicon (Sn, Sb, Ge)-based lithium/sodium-ion battery alloying anodes. Small Methods 2020;4:2000218.

99. Tian H, Xin F, Wang X, He W, Han W. High capacity group-IV elements (Si, Ge, Sn) based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. J Materiomics 2015;1:153-69.

100. Yin L, Song J, Yang J, et al. Construction of Ge/C nanospheres composite as highly efficient anode for lithium-ion batteries. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 2021;32:6398-407.

101. Hu Z, Zhang S, Zhang C, Cui G. High performance germanium-based anode materials. Coord Chem Rev 2016;326:34-85.

102. Jung H, Allan PK, Hu Y, et al. Elucidation of the local and long-range structural changes that occur in germanium anodes in lithium-ion batteries. Chem Mater 2015;27:1031-41.

103. Loaiza LC, Monconduit L, Seznec V. Si and Ge-Based Anode Materials for Li-, Na-, and K-Ion Batteries: A Perspective from Structure to Electrochemical Mechanism. Small 2020;16:e1905260.

104. Wen N, Chen S, Feng J, et al. In situ hydrothermal synthesis of double-carbon enhanced novel cobalt germanium hydroxide composites as promising anode material for sodium ion batteries. Dalton Trans 2021;50:4288-99.

105. Zeng T, He H, Guan H, Yuan R, Liu X, Zhang C. Tunable hollow nanoreactors for in situ synthesis of GeP electrodes towards high-performance sodium ion batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed 2021;60:12103-8.

106. Liu R, Luo F, Zeng L, et al. Dual carbon decorated germanium-carbon composite as a stable anode for sodium/potassium-ion batteries. J Colloid Interface Sci 2021;584:372-81.

107. Yang Q, Wang Z, Xi W, He G. Tailoring nanoporous structures of Ge anodes for stable potassium-ion batteries. Electrochem Commun 2019;101:68-72.

108. He C, Zhang JH, Zhang WX, Li TT. GeSe/BP van der waals heterostructures as promising anode materials for potassium-ion batteries. J Phys Chem C 2019;123:5157-63.

109. Zhou Y, Zhao M, Chen ZW, Shi XM, Jiang Q. Potential application of 2D monolayer β-GeSe as an anode material in Na/K ion batteries. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2018;20:30290-6.

110. Hao J, Wang Y, Guo Q, Zhao J, Li Y. Structural strategies for germanium-based anode materials to enhance lithium storage. Part Part Syst Charact 2019;36:1900248.

111. Balogun M, Yang H, Luo Y, et al. Achieving high gravimetric energy density for flexible lithium-ion batteries facilitated by core-double-shell electrodes. Energy Environ Sci 2018;11:1859-69.

112. Mo R, Rooney D, Sun K, Yang HY. 3D nitrogen-doped graphene foam with encapsulated germanium/nitrogen-doped graphene yolk-shell nanoarchitecture for high-performance flexible Li-ion battery. Nat Commun 2017;8:13949.

113. Seo M, Park M, Lee KT, Kim K, Kim J, Cho J. High performance Ge nanowire anode sheathed with carbon for lithium rechargeable batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2011;4:425-8.

114. Li D, Feng C, Liu HK, Guo Z. Hollow carbon spheres with encapsulated germanium as an anode material for lithium ion batteries. J Mater Chem A 2015;3:978-81.

115. Kim D, Park C. Co-Ge compounds and their electrochemical performance as high-performance Li-ion battery anodes. Mater Today Energy 2020;18:100530.

116. Zhao Z, Ma W, Wang Y, Lv Y, Ma C, Liu X. Boosting the electrochemical performance of nanoporous CuGe anode by regulating the porous structure and solid electrolyte interface layer through Ni-doping. Appl Surf Sci 2021;558:149868.

117. Bensalah N, Matalkeh M, Mustafa NK, Merabet H. Binary Si-Ge Alloys as high-capacity anodes for Li-ion batteries. Phys Status Solidi A 2020;217:1900414.

118. Doherty J, McNulty D, Biswas S, et al. Germanium tin alloy nanowires as anode materials for high performance Li-ion batteries. Nanotechnology 2020;31:165402.

119. Rodriguez JR, Qi Z, Wang H, et al. Ge2Sb2Se5 glass as high-capacity promising lithium-ion battery anode. Nano Energy 2020;68:104326.